ELSA OLIVEIRA is a PhD student at the African Centre for Migration & Society (ACMS) at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. She is interested in the ways that research can support social justice issues, specifically in the areas of migration, sexuality, gender and health.

Migration in South Africa

People across the globe move within borders and across countries for a wide variety of reasons. Some movement is forced—the result of political conflict, wars, and environmental disasters—but the majority of migration is linked to the search for improved livelihood from rural and peri-urban communities to urban centers. While the percentage of the world’s population that are migrants has remained fairly steady[1], the World Bank estimates that the amount of remittances has greatly increased, from 132 billion U.S dollars in 2000 to 440 billion in 2014[2]. This increase highlights the fact that migration is a critical livelihood strategy for many people and families.

Recent census data in South Africa indicates that the majority of its migrant population moves internally, with people primarily moving to urban centers in search of improved economic opportunity[3]. In line with global trends, South Africa’s cross-border migrant population makes up approximately 3.3% of the total populace, with the majority of migrants living in Johannesburg, South Africa’s largest and wealthiest city.

Research conducted at the African Centre for Migration & Society (ACMS)[4] shows that cross-border migrants face an increased risk of xenophobia in the form of police harassment, stigma, and discrimination[5] [6] [7]. As a result of an often hostile social, political, and economic environment, many cross-border migrants, especially those engaged in illegal activity such as sex work, choose to remain hidden in the city and are often under-represented in research and policy debates[8].

Research and Partnership through Visual and Narrative Methodologies: MoVE

Official Invitation to Volume 44 Exhibition launch

Researchers at the ACMS that work with presumed ‘hard to reach’ urban groups, such as migrant sex workers, informal traders, and LGBTIQ[9] asylum seekers, have begun to search for innovative research methods that can facilitate increased insight into the complex lived experiences of individuals and communities.[10] [11] [12] Since 2006 the ACMS has explored the use of visual and narrative methodologies and projects alongside more traditional qualitative research methods.

Primrose: Many migrants left children back home. I came to Johannesburg so that I could earn money and send the money back home.

These projects co-produce knowledge through the development of partnerships with migrant groups, especially those who are under-represented in research and public policy debates, and who often face multiple vulnerabilities. The ACMS has partnered with residents in informal settlements and hostels, with inner-city migrants, with LGBTIQ asylum seekers and refugees, and with migrant men, women and transgender persons engaged in the sex industry. These partnerships have culminated in a range of research and advocacy outputs, including community-based exhibitions, public exhibitions, and engagement with officials[13]. Furthermore, the outputs produced during several of the visual and narrative projects have been utilized in a range of reports[14], mainstream media publications[15], blogs[16], and popular media[17].

In 2013, Dr. Jo Vearey and I launched the MoVE project in order to begin to explore the efficacy of such methods and their resulting research and advocacy projects. MoVe[18] is a home for research projects conducted at the ACMS that utilize ‘innovative methods’ such as visual and narrative methods, and explore a range of issues including migration, sexuality, gender, and health. MoVE aims to integrate social action with research, and involves collaboration with migrant participants, existing social movements, qualified facilitators and trainers, and research students engaged in participatory research methods. This work includes the study and use of visual method—including photography, narrative writing, participatory theatre, collage, and other arts-based approaches—in the process of producing, analyzing, and disseminating research data.[19]

Tafadzwa: My father came from Zimbabwe to work at this mine, and now the mine has been closed and my father has since passed away. I too came to Musina to look for employment just like my father.

Tafadzwa: My father came from Zimbabwe to work at this mine, and now the mine has been closed and my father has since passed away. I too came to Musina to look for employment just like my father.

Researchers that utilize visual and narrative methods are often interested in direct engagement with social justice issues/movements where the research project involves, “communicating information about the experiences associated with differences, diversity, and prejudice”[20]. These researchers often work closely with community-based organizations and under-represented groups of people in marginalized settings[21] [22] [23]. The nature of the methodology of work results in the creation of an ‘artifact’ during the research process—a poem, photograph, exhibition, drawing or performance. These ‘artifacts’ are often shared in multiple platforms, reaching beyond traditional academic practices of dissemination to reach a greater diversity of audiences. O’Neil argues that, “renewed methodologies can transgress conventional or traditional ways of analyzing and representing research data.”[24] As media and cyber platforms continue to be developed and made available to global audiences, researchers interested in visual and narrative methods increasingly have more opportunities whereby they can share the work, knowledge, and practice that emerges from such projects.[25]

Timzela: Train tracks near the Musina mall. The drivers have been loyal customers for years

Timzela: Train tracks near the Musina mall. The drivers have been loyal customers for years

Researchers that utilize visual and narrative methods also ‘capture’ data that emerges during and after workshops, usually in the form of narrative interviews, to explore the specific issues and areas of concentration that pertain to their research study. For example, the Working the City project, which formed the basis of my MA study, sought to explore how migrant sex workers who lived in inner-city Johannesburg (re)presented themselves during their transition to an urban space. The primary phase of my data collection took place via observation during the workshop process, photo storytelling, and group discussions. When the project was completed, I conducted semi-structured narrative interviews where the images were used as prompts to further narrative inquiry, otherwise known as ‘photo-elicitation’[26]. Collier and Collier suggest that images invite people to take the lead in inquiry, making full use of their expertise. They also propose that “psychologically, the photographs on the table perform as a third party in the interview session”[27], whereby researcher and study participant can explore the images together. During the photo-elicitation phase of my research, important insights into issues of power and group dynamics became evident.

Skara: Foreigners accused of selling at a low price.

Skara: Foreigners accused of selling at a low price.

Some participants chose not to share certain information about their personal lives and/or the internal dissonance that they felt regarding their line of work with the group, but they felt comfortable speaking candidly about these issues during the one-on-one interviews. Sbu, a cross-border migrant from Zimbabwe stated:

I don’t like to speak too much about my work. I am not proud of what I do. I am a Christian and I don’t think that what I do is ok but it is what I do for my family. If I speak too much with these people [other participants] then they will know too much about me and that is not necessary. I like the workshop too much but I have my way of working in this space that is for me okay (Sbu, 2010).

This multi-method approach, I believe, offered me insights into the issues that I was exploring that other traditional qualitative methods alone might not have been able to offer. The photo-elicitation phase of my study highlighted the importance of interrogating the data collected during group work. In many ways, the workshops offered me an important understanding of the broad and often shared experiences of participants, but it was during the narrative interviews that I gained the level of insight into representation that I was hoping for. I don’t believe that I would have been able to delve into the array of feeling and complexity had I not used both methods: participatory visual methods and photo-elicitation interviews.

Participants in Musina writing on the ‘Wall of Words’.

Participants in Musina writing on the ‘Wall of Words’.

Challenges Facing Those in the Sex Industry

Sex work is currently illegal in South Africa. According to section 20(1A)(a) of the Sexual Offences Act, Act 23 of 1957, all parties engaged in the buying and selling of sex are committing a crime. The Act reads as follows:

- Persons living on earnings of prostitution or committing or assisting in commission of indecent acts. (1A) Any person 18 years or older who …. (a) has unlawful carnal intercourse, or commits an act of indecency, with any other person for reward…shall be guilty of an offence” [28]

Despite the fact that the sex industry provides an important, albeit informal, livelihood strategy for many adult men, women and transgendered individuals, existing research clearly shows that the current legal framework negatively impacts the safety and well-being of involved individuals. [29] [30] [31]

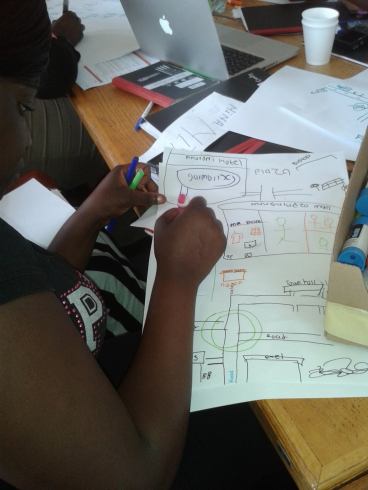

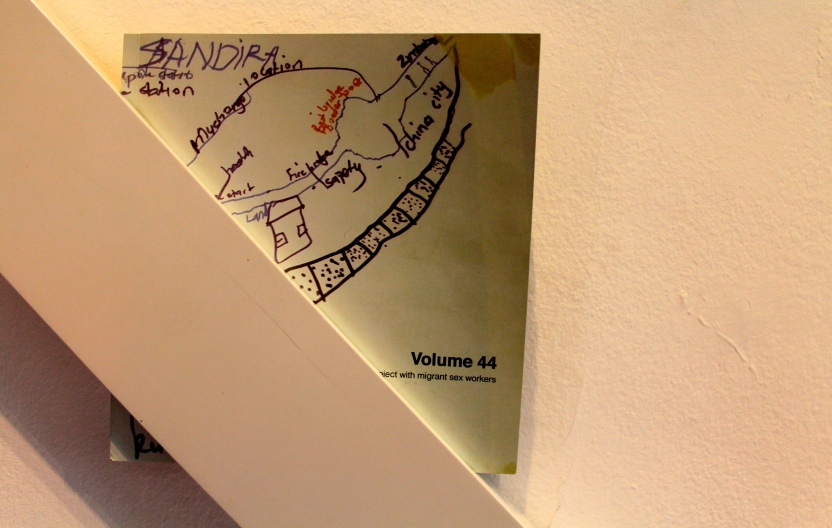

This image shows a participant completing a ‘mapping exercise.’ During this exercise, participants were asked to reflect on a series of themes (e.g. family, danger, health, fear, happiness, etc.) and how the themes connected to the places/spaces that they occupied (or not).

This image shows a participant completing a ‘mapping exercise.’ During this exercise, participants were asked to reflect on a series of themes (e.g. family, danger, health, fear, happiness, etc.) and how the themes connected to the places/spaces that they occupied (or not).

Much previous research has focused on the experiences of female sex workers, and indicates that the challenges experienced range from difficulties in accessing public services, including healthcare, to police brutality and violence at the hands of clients[32] [33]. Whilst estimates of the numbers of individuals engaged in the sex industry in South Africa are lacking, existing research shows that the industry is composed of both South African nationals and foreign-born migrants. In a study conducted in 2010 across four sites in South Africa—Cape Town, Sandton (northern Johannesburg), Hillbrow (inner-city Johannesburg), and Rustenburg (outskirts of Johannesburg)—51.9 percent of sex workers surveyed identified as cross-border migrants. [34]

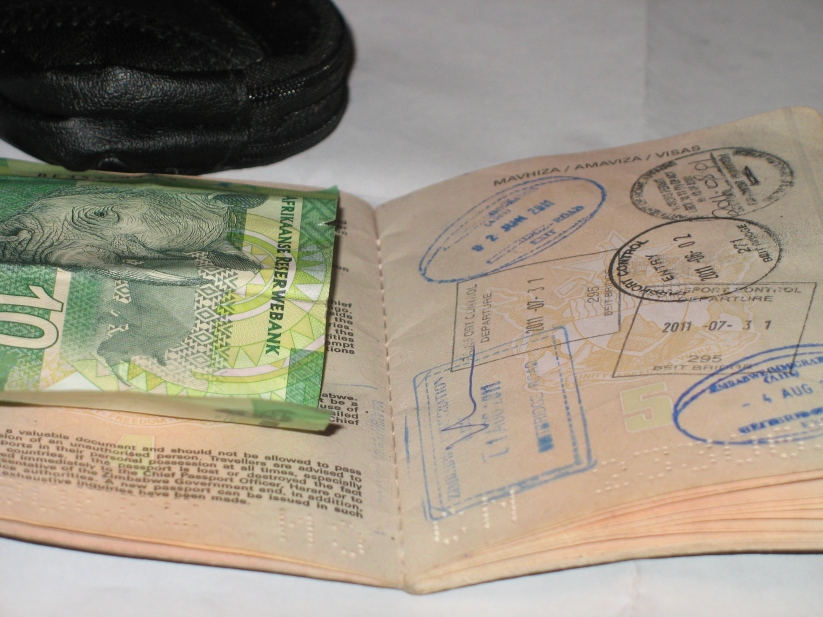

Images that were taken and selected by participants were printed each week so that participants could engage with the images as they worked on their stories.

The Project: Volume 44

In 2014, the MoVE Project completed Volume 44[35], a participatory photo project undertaken with migrant men, women and transgender sex workers living and working in South Africa. The project worked with nineteen internal and cross-border migrants from Zimbabwe who were selling sex in inner-city Johannesburg and Musina, a rural South African town on the Zimbabwean border. The project was supported via collaboration between the African Centre for Migration & Society (ACMS) at Wits University, the Sisonke Sex Worker Movement, and the Market Photo Workshop (MPW). The basis of this collaboration included the previous research conducted at the ACMS with both Sisonke and the MPW, as well as the shared interest in addressing social justice issues and exploring the ways in which the visual (photography) could make these issues ‘visible.’

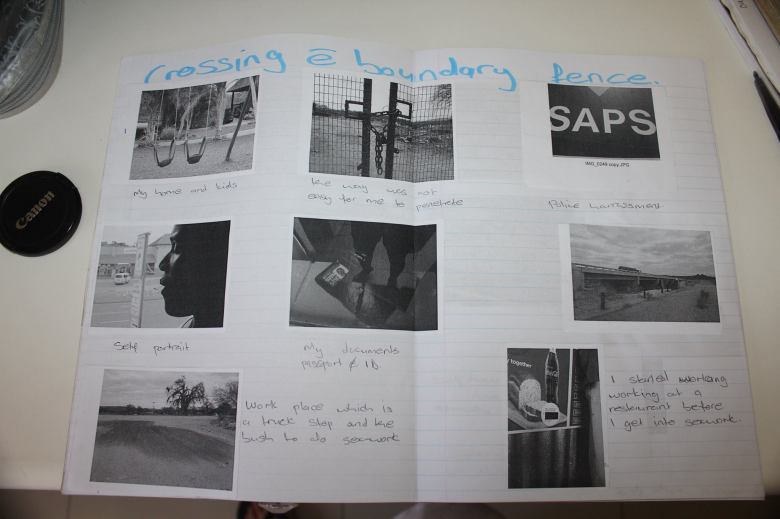

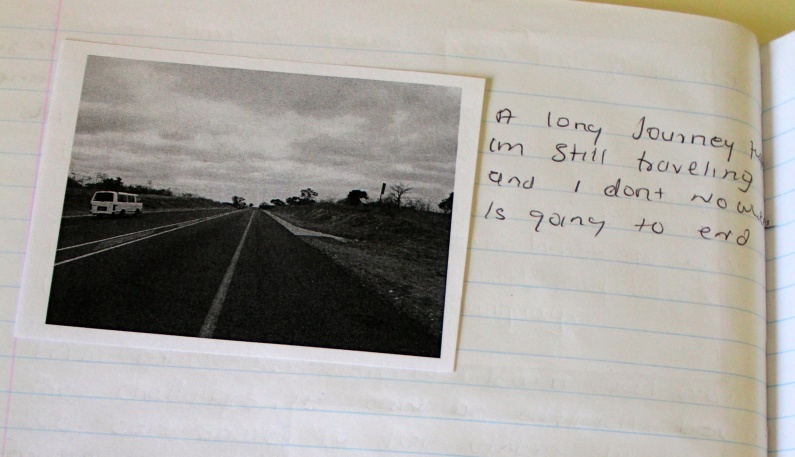

A storyboard created by a participant with images that she had taken up until this point of the workshop.

A storyboard created by a participant with images that she had taken up until this point of the workshop.

Volume 44 was informed by the former ACMS project Working the City (2010). After the Working the City project, the collaborating partners came together to discuss the strengths, challenges, and shortcomings of the project in order to inform future collaborative work. Sisonke highlighted the need to include a greater representation of sex workers in South Africa, the MPW stressed the importance of increasing visual literacy training for participants, and the ACMS believed that it was necessary to explore issues of migration and sex work outside of Africa’s urban hub in order to gain a deeper understanding of the issues under investigation. In 2013, the Open Society Foundation of South Africa (OSF-SA) granted the ACMS, in partnership with the MPW and Sisonke, the funding to conduct a year-long project that involved migrant men, women, and transgender sex workers in the Gauteng and Limpopo Provinces of South Africa.

Prior to the commencement of the project, prospective participants were identified by Sisonke and were invited to attend an initiation meeting with the research team. During this meeting, participants learned about the project and of the risks and benefits of their participation in the study. Information sheets that included contact details were distributed and an opportunity to ask questions was provided. Participants learned that they would be taught basic photography skills and that they would be asked to keep a daily journal that captured their reflections, stories, and narratives. They were also informed that the journals would be used as data for research, and that they would be given an opportunity to remove pages that they did not want included prior to the collection of journals at the end of the project. Additionally, participants learned that part of their involvement in the workshop meant that they would be guided, with the support of the facilitators and the research team, to create a ‘photo story.’ This story would consist of a narrative account and ten images, with accompanying captions, that would be shared with the general public. Individuals who were keen to participate provided verbal consent.

Participants glued their images onto their journals and wrote captions.

Participants glued their images onto their journals and wrote captions.

An important shortcoming identified during the Working the City project was that participants hadn’t been offered the opportunity to create a ‘private’ visual story; a story that was possibly important for them to create, but that would remain inaccessible in the public domain. As a result, participants in Volume 44 were encouraged to produce a ‘private story’ that would be exhibited during the last day of the workshop. Many of these ‘private stories’ were similar to those that they had selected for the public, with slight variations such as a greater diversity of images, the absence of pseudonyms, and inclusion of identifying information. Others choose to tell a completely different story. In these cases, the stories tended to consist of highly traumatic events that had taken place in their lives, such as experiences of rape, loss of children, or issues that highlighted family distress. In the telling of these private visual stories we can begin to unpack issues of representation and the ways that ‘the public’ is viewed by participants.

During the final phase of the workshop participants sat with the workshop facilitator individually to discuss their final image, caption, and narrative selections for both their public and private exhibitions. Although photographic techniques to address issues of anonymity were central throughout the workshop, increased attention to these concerns was given during the final editing phase, with special scrutiny paid to the information that was selected for the public. During this phase, the workshop facilitator made every attempt to identify information that could possibly negatively impact the participants or the sex worker community.

Vearey insists that caution be implicit when using visual methodologies, and encourages researchers to be mindful when exposing individuals’ ‘hidden spaces’ and their communities.[36] Kihato urges us to consider the camera as a ‘disempowering tool’ given the possible dangers of making migrant women’s lives visible[37]. Therefore, in an effort to maximize the anonymity and safety of participants, images and text that included identifying information such as places of work and names of people, were altered, deleted, or replaced with other images or names. Lessons learned from the Working the City project also drove this level of editing interrogation. The project participants had been informed that their work would culminate in a public exhibition, but once the project ended and requests were made by various community organizations to showcase the work, many participants rejected the idea of displaying the exhibition in their communities out of fear of being identified as sex workers. While at times the editing process felt restrictive to participants of Volume 44, the participants’ potential lack of understanding of what it means to ‘go public’ made this a necessary process for the research team.

The official Volume 44 public exhibition was held at the MPW in May 2014[38]. The exhibition highlighted the multiple layers of the project by featuring aspects of the multimodal visual and narrative approaches[39]. All nineteen participants attended this workshop and stated that they were proud of the work that they produced as individuals, and collectively. During the exhibition, Babymez, a migrant sex worker from KwaZulu Natal that currently lives in Johannesburg, expressed pride in witnessing the public engage with her work:

This is too nice. I never think that anyone wants to hear my story but look—so many people are here to know what sex workers’ lives are like. My story is not about sex work but it is important because it is my life and I don’t think that anyone has ever asked me about my life.

Volume 44 is only one example of the various MoVE projects that support not only the production of powerful stories by a group of individuals who are both under-represented and highly marginalized, but also facilitate a space in which the participants[40] and the research team have the opportunity to reflect on their lives and the world around them. Although these types of methods are not always applicable to all research projects, and are certainly better suited for some research studies than others, what is evident is that they are afforded the time to think about what it means to tell and share stories.

A sneak peek into the curated exhibition.

A sneak peek into the curated exhibition.

As a researcher, part of my job is to write ‘stories’ about ‘others,’ and in doing so I attempt to create knowledge about others’ experiences and issues. These methods, for a range of reasons that have already been highlighted in this paper, offer the researcher an opportunity to engage in the ‘feel’ of events and lives. They offer the possibility to engage participants in the production of knowledge, and they support the production of materials that can be disseminated as non-traditional academic outputs. Equally important, however, is the fact that these methods, and projects like Volume 44, highlight the need to consider the subjectivity of knowledge and the power inherent in the production of knowledge: Who is producing knowledge and why? How does the production of ‘knowledge’ supports and/or limits what we ‘know’ and what we believe? The possibility of narratives being diluted when presented, or the potential for participants to intentionally select only stories that they want out in the world, are problematic when considering the benefits and drawbacks of many methodological practices, not solely with the use of ‘innovative methods’. The interrogation of research, from inception to dissemination of findings and ‘stories’ that we as researchers produce, must ‘live’ in a more fluid space where knowledge is accepted as complex and where “the subjective is neither unified nor fixed” (Weedon 1987:22). Visual and narrative methodologies offer an opportunity to engage with various theoretical and epistemological frameworks. While utilizing these methods is not without incredible logistical challenges, what remains central is that participants seem to value their involvement in these projects.

Image of the Volume 44 Publication.

Image of the Volume 44 Publication.

Teresa, a South African participant from Musina stated,

It’s too good for me to be able to think about my life. I never think that someone want to hear my story. I mean–who am I to tell my story? But you come and now you want to know and I get to think about my story and my life and all of the things that I live to tell about. I want everyone to hear my story because I am not the only one who has these experiences. I am a person like everyone else and even though I face too many challenges because of the police harassment and violence and because I am not a South African, I am strong and I am alive and I think that this project has helped me learn more about who I am. I think about story so different now. I am too happy to be a part of this project.

Chantel, a participant from Johannesburg, wrote in her journal,

Telling my story is so powerful for me. Everyday I look forward to writing or thinking about my story. I want to take images that show the way that sex workers are treated. That I am a person. This project let me do this. It helps me to take away stress and to know that I am not alone. I am so grateful.

To learn more about Volume 44 and to download a free copy, please visit our online publication. For more information on past, current, and upcoming MoVE projects please visit us on our Weblobg [41] and follow us on Tumblr[42] , Facebook[43] , Twitter[44] and Instagram.[45]

[1] According a report released by the International Organization for Migration (IOM) in 2012, there were 214 million migrants in world in 201. See International Organization for Migration (IOM). “Counter Trafficking and Assistance to Vulnerable Migrants.” IOM Annual Report of Activities, 2011.

[2] Migration and Remittances: Recent Developments and Outlook Special Topic: Forced Migration. 2014. http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTPROSPECTS/Resources/334934-1288990760745/MigrationandDevelopmentBrief23.pdf .

[3] Stats South Africa. Quarterly Labour Force Survey: Quarter 3, 2012. Accessed Jan 7, 2015.

http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/statsdownload.asp?PPN=P0211&SCH=5367.

[4] The African Centre for Migration & Society is an interdisciplinary African-based Centre dedicated to research on human mobility and social transformation. http://www.migration.org.za.

[5] Landau, Loren, “Living Within and Beyond Johannesburg: Exclusion, Religion, and Emerging Forms of Being,” African Studies Review 68(2) (2009): 197-214.

[6] Richter, M, Chersich MF, Temmerman M and Luchters S, “Characteristics, sexual behaviour and risk factors of female, male and transgender sex workers in South Africa,” South African Medical Journal 103(4) (2013) :246-251.

[7] Vearey, Jo, “Migration, urban health and inequality in Johannesburg”. In: Migration and Inequality ed Bastia, T. (Ed). (Routledge: London, 2013), 121-144.

[8] Vearey, Jo, “Hidden spaces and urban health: exploring the tactics of rural migrants navigating the City of Gold,” Urban Forum 21(1) (2010): 37-53.

[9] LGBTIQ is an acronym for: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Intersex and Queer.

[10] Oliveira, Elsa. “Migrant women in sex work: does urban space impact self (re)presentation in Hillbrow, Johannesburg” (MA diss, University of the Witwatersrand, 2011).

[11] Schuler, Greta. “At Your Own Risk: Narratives of Zimbabwean Migrant Sex Workers in Hillbrow and Discourses of Vulnerability, Agency, and Power” (MA diss, University of the Witwaterand, 2013).

[12] Vearey, Hidden spaces and urban health, 37-53.

[13] Several MoVe projects have been selected to participate in local, national, and international advocacy and research initiative meetings. These projects have been showcased in public spaces, at art festivals, and at local and international conferences as a tool to share information, ignite discussion, and promote reflection on issues otherwise not readily available for public consumption. Exhibitions have been displayed at NGOs such as the South African Human Rights Commission, and have travelled to Durban, South Africa; Kampala, Uganda; Rio de Janeiro and Minas Gerais, Brazil; Amsterdam, Netherlands; Portland, Oregon/USA; Buenos Aires, Argentina; Bogota, Colombia, and Kolkata, India, to name a few.

[14] Oliveira, Elsa and Lety, Diputo “A short Story about being a sex worker in Hillbrow: Living with HIV and how I treat myself” in Hospice Palliative Care Association of South Africa Law Manual Chapter 10 (2012), accessed on March 10, 2015. http://www.hpca.co.za/Legal_Resources.html.

[15] Tormey, Jane. Cities and Photography. (Routledge. 2012). http://www.routledge.com/books/details/9780415564403/.

[16] African Sex Worker Alliance (ASWA) Website, October 2012. http://africansexworkeralliance.org/stories/working-city-experiences-migrant-women-inner-city-johannesburg-pictorial-narratives-migrant-.

[17] Kreutzfeldt, Dorothee and Malcomess Bettina. Not No Place. Jacana Press. 2013.

[18] http://www.migration.org.za/weblog/move.

[19] Ibid, 2015.

[20] Leavy, Patricia, “Method Meets Art: Arts-Based Research Practice’ (The Guildford Press, 2009), 13.

[21] O’Neil, Maggie, ‘Renewed methodologies for social research: ethno-mimesis as performative praxis’, The Sociological Review, 50.1, pp. 69-88. 2002.

[22] Vearey, J, Oliveira, E., Madzimure, T and Ntini, B, “Working the City: Experiences of Migrant Women in Inner-city Johannesburg,” The Southern African Media and Diversity Journal, 9 (2011): 228-233.

[23] Wang, Caroline and Burris, Mary Ann, “Photovoice: concept, methodology and use for participatory needs assessment,” Health Education & Behaviour 24 (1997): 369-387.

[24] O’Neil, Maggie, “Renewed methodologies for social research: ethno-mimesis as performative praxis,” The Sociological Review 50 (1) (2002): 69.

[25] Leavy, Patricia, “Method Meets Art: Arts-Based Research Practice’, 2009.

[26] Oliveira, E. “Migrant women in sex work: does urban space impact self (re)presentation in Hillbrow, Johannesburg”, 2011.

[27] Collier, John and Collier Malcom, “Visual Anthropology: Photography as a Research Method” (University of New Mexico Press 1986), 105.

[28] SAFLII. South African Law Commission. 2010.

[29] Richter et al. Characteristics, sexual behaviour and risk factors of female, male and transgender sex workers in South Africa, 246-251.

[30] Scorgie, F, Nakato, D., Harper, E., Richter, M., Maseko, S., Nare, P., Smit J., Chersich M.F. “’We are despised in the hospitals’: Sex workers’ experiences of accessing health care in four African countries,” Culture, Health and Sexuality 15(4) (2013): 450-65.

[31] Vearey, Migration, urban health and inequality in Johannesburg, 2013.

[32] Richter, et al. Characteristics of behavior, 2013.

[33] Scorgie, F, Nakato, D., Harper, E., Richter, M., Maseko, S., Nare, P., Smit J., Chersich M.F. “’We are despised in the hospitals’: Sex workers’ experiences of accessing health care in four African countries,” Culture,Health and Sexuality 15(4) (2013): 450-65.

[34] Richter M., Luchter S., Ndlovu D., Temmerman M., Chersich MF, “Female sex work and international sport events – no major changes in demand or supply of paid sex during the 2010 Soccer World Cup: a cross-sectional study,” BMC Public Health. 12 (2012); 12:763

[35] Ethics Clearance: The research study received ethics approval from the University of the Witwatersrand Ethics Committee, and all photographers signed a consent form for the use images by the African Centre for Migration and Society, Market Photo Workshop, and Sisonke Sex Worker Movement.

[36] Vearey, Hidden spaces and urban health, 51.

[37] Kihato, Caroline, “invisible lives, inaudible voices? The social conditions of migrant women in Johannesburg” African Identities, 5(1) (2007): 89-110.

[38] http://www.marketphotoworkshop.co.za/exhibitions/entry/volume-44-exhibition2.

[39] http://www.migration.org.za/page/official-public-exhibition-vol44/move.

[40] Anonymity: Research participants in this study were anonymous, with the exception of two who opted to use pseudonyms. Therefore, the names that appear in the photo credits are not the actual names of the participatory photo project participants.

[41] http://www.migration.org.za/page/official-public-exhibition-vol44/move

[42] www.methodsvisualexplore.tumblr.com

[43] https://www.facebook.com/themoveprojectsouthafrica

[44] www.twitter.com/movesafrica