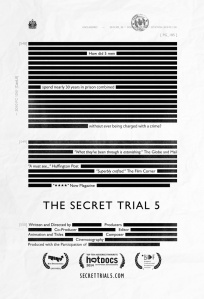

“How did 5 men spend nearly 30 years in prison combined without ever being charged with a crime?”

Secret Trial 5 [1] is a fascinating film which explores the use of a problematic provision in Canadian immigration legislation. Security certificates are a tool that allows the Canadian government to deport non-citizens it deems a threat to national security. The security certificates process is one in which the allegations and evidence held against the detainees are never fully revealed to the accused person, and significant parts of their trials are held in secret.

Secret Trial 5 [1] is a fascinating film which explores the use of a problematic provision in Canadian immigration legislation. Security certificates are a tool that allows the Canadian government to deport non-citizens it deems a threat to national security. The security certificates process is one in which the allegations and evidence held against the detainees are never fully revealed to the accused person, and significant parts of their trials are held in secret.

Secret Trial 5 explores the impact of this provision on the lives of 5 men: Adil Charkaoui, Hassan Almrei, Mahmoud Jaballah, Mohamed Harkat, and Mohammad Zeki Mahjoub.

The Director and Producer, Amar Wala, is an emerging filmmaker based in Toronto, Canada. He was born in Bombay, India, and moved to Toronto with his family at the age of 11. The Secret Trial 5 is Amar’s first feature film. In November 2014, Amar Wala sat down with ESPMI’s Petra Molnar to discuss the film and its wider implications.

Amar, what inspired you to make the Secret Trial 5? Was there a particular person or a story that inspired you to pursue this issue further?

I made a short film about one of the families while I was in film school. Around the time I was editing this film in 2007, the Supreme Court of Canada came out with the decision that deemed the security certificate program unconstitutional. As a result, the Canadian Government introduced Bill C-3 in 2008 and the men were moved to house arrest from detention.

Everyone including myself thought this was much better and that it was the beginning of the end of the system. Unfortunately it was not and in 2009 one of the subjects, Mr. Mohammad Zeki Mahjoub, actually asked to be returned to prison, stating that the house arrest conditions were unbearable. This is what piqued my interest and I felt like I needed to know more about these house arrest conditions. Mr. Mahjoub was in prison for a long time and fought really hard to get out. For someone like that to actually willingly go back to jail made me wonder how bad the house arrest conditions actually were. That is what I had to look into. This was the trigger point for the film.

In the film, you state that Mr. Majoub was the one subject that did not want to participate in the project. Why do you think this is?

We filmed with him quite a bit early on in the process and he always reserved the right to not make his final decision until he was ready to bring his story forward. And in the end he chose not to be in the film because perhaps he felt like this was not the best way to tell his story. The men are all different and very unique people. Their cases are not connected, and for Mr. Mahjoub, perhaps presenting all of their stories together was not the best way to proceed. We wanted him in the film quite badly, but in the end it was his choice and we respected that.

I understand that you were crowd-funded for this film. How did this come about?

This came out of necessity. We started filming in 2009 and we basically pitched the idea to everyone, including the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, The Canadian Film Board and every documentary outlet you could think of. At that point, the recession was hitting everyone pretty hard and documentary funding had been cut quite dramatically in Canada. For a first time filmmaker to be making a film about quite a controversial topic, the odds were not in our favour.

We had to look at alternative means and crowd-funding was just beginning at that point. A film called The Age of Stupid, which was a British documentary about climate change, had done this quite successfully. They had created a website and encouraged people to donate, and were very successful with it. We thought that we could model ourselves after them and do something like that with a human rights issue. The gamble worked and it got us the first $20,000, on which we shot a lot of the film.

Your film deals with a fairly controversial topic and yet you managed to get quite a lot of support for it. Why do you think this is?

When you break the topic down for people, it’s really not controversial. It’s controversial if you simply look at it from a “he said/she said” or a “terrorist/not a terrorist” point of view. What we did was try to appeal to basic principles in people, such as the principle that a person should never be in prison without a charge and not have access to a defense under any circumstances. People agreed with this. We explained how convoluted and crazy the process was and that this was happening here, in our country. We never talk about these issues as a nation, and I think that resonated with people.

Your film was a very interesting portrayal of some of the tensions in Canada today. There is tension between the notion that Canada is a welcoming place with all sorts of higher values yet at the same time, since 9/11, there has been increased securitization and the closing of borders. How do you see the security certificates regime fit into this framework?

I think it’s definitely rooted in immigration policy as a whole. The problem is that immigration issues are not something that we talk a lot about as a nation. We have marketed ourselves and convinced ourselves that we are definitely this welcoming and multicultural society that works hard to integrate new immigrants, but that is not always true. We do a very good job of hiding the ugly side of immigration.

For example, deportations overall are on the rise. We deported somewhere around 15,000 people last year, which is a very high number for a country the size of Canada. We also do not acknowledge our own colonial history and the fact that this is a country built and sustained on immigration. Also, we have not made amends with our indigenous peoples. These are all part of the same colonial history of Canada. We are all really immigrants here, unless you are an indigenous person. We all arrived at some point. Unfortunately, this is a conversation that is just beginning.

These issues that are raised in the film are not easy to get people to care about. It is not easy to get people to care about immigrants. We often pretend that we are a thoughtful and caring community but our history says otherwise. Getting people to care about refugees and people in detention is a very difficult fight but it is a fight that we need to have.

Ultimately, migration and movement are not seen as human rights. That hopefully will come one day but we have a history as a planet in which certain part of the world have been ravaged and certain parts have thrived. We haven’t really come to terms and acknowledged this yet. This profound inequality, in a way, is at the root of all of these issues. It is not a coincidence that every single one of the Secret Trial 5 was a Muslim man. This did not happen by accident. You are seeing particularly this Conservative Government engage further with these issues of identity and who is allowed to be Canadian, going as far as to strip people who have been born here of citizenship.

Do you think that 9/11 was a catalyst for these more draconian measures or would they have been introduced anyway?

9/11 certainly sped up some of the more draconian measure that you are seeing in western society for sure. 9/11 made the regime a lot worse. For example, Mr. Mahjoub and Mr. Mahmoud Jaballah were both first arrested before 9/11. However, the first time Mr. Jaballah was arrested on a security certificate, he won his case and was in jail for only 7 months. Then 9/11 happened after the second time he was arrested and he remained in jail for 7 years. 9/11 definitely had an impact in exacerbating the issue but it is not the root cause. However, the root goes much deeper than that.

How do you try to work against some of these discourses that go so much deeper?

This will happen slowly over time. I think the problem is that these discourses happen in academic settings and don’t reach out to the general public. However, the general public is full of thoughtful, caring people. Unfortunately, it is sort of difficult to shake them out of a certain sense of apathy. If you speak to them on a human level, they do respond to the issues that you are presenting. I think the film is proof of this. The vast majority of people who see the film did not know about this regime in any way and yet they are angry about how this was allowed to happen. That’s something that we are not good at as Canadians – getting angry. I think we need to get better at this.

Where do you see the role of the judiciary and the courts in all this?

This is tricky. I was quite disappointed in the recent Supreme Court of Canada decision this year [the case of Mohamed Harkat, which reaffirmed the constitutionality of the security certificate regime, with the use of special advocates, top-secret, security-cleared, private lawyers who are independent of government. These lawyers have access to part of the file against the accused, but who are still not allowed to communicate the basis of the charge to the person against whom the security certificate is enacted]. The lawyers who actually argued the case and the people in the academic community expect these kinds of decisions because they see the history of the judiciary deferring to parliament on these issues. Unfortunately, judges don’t want to deal with national security issues. This is a problem, because they should be dealing with precisely these types of issues and they have to deal with the rights of these people.

Security certificates in particular will be on the books for some time now. I don’t think anyone is going back to the Supreme Court anytime soon. However, the government is not using security certificates anymore as a tool. They are problematic from an efficiency standpoint, apart from all the human rights problems. I don’t know if this is a good thing or if it is a direct result of judicial decisions that gave more protections to the individual person.[2] I don’t know that judicial decisions have helped as much as time has helped. However, I do think that I would have preferred that the judges and in particular the SCC would have been more aggressive in their decision making. They found the regime unconstitutional in 2007, and they should have read the law as stating that this regime should no longer be on the books.

Often the judiciary and the law move at a slower pace than we would like. Why do you think this is?

The question I have always had is: “Is this historically the kind of decision that Canada makes when it comes to its citizen/non-citizen record?” There is nothing in the Charter of Rights and Freedoms about having to be a being a citizen to have access to basic rights. There are at any given point in Canada millions of people who are immigrants and not technically citizens yet. When you have a county that is built like this, does it make sense to have a law that is not sympathetic to such a significant portion of the population? That is something that the Supreme Court did not even address, which was very disappointing.

Law often operates on a national level instead of looking at issues in a global way. How do you see these more global regimes governing the flow of people playing out?

There needs to be more information provided to the general Canadian public about issues like this. My skills as filmmaker help in that sense. I think that these stories and issues are complex and sometimes you have to break them down to a more basic level and use the power of art to really understand why this is important to get people emotionally engaged in some way. I think this is why Secret Trial 5 is having an impact, even though it is a very small impact.

I think people are seeing the actual pain that is caused to the individual person. We have gotten to a point where the principle on its own doesn’t engage people anymore. Everyone is going to agree that we shouldn’t illegally deport people to Somalia but we don’t seem to get engaged about it. I think English Canada in particular is not very good at political participation beyond the general parliamentary voting structure. I think that we have lost the ability as a country to get involved in issues and we actually scoff at people when they do get engaged. We see that as a weakness. I don’t know if this has always been the case in Canada but it is something that we need to shake ourselves out of, because political apathy is a very dangerous thing.

Was there anything that surprised you when you were making this film?

There were a few things. It definitely surprised me how thoughtful, intelligent, and funny the men were. I was expecting to have a much harder time to break through walls to establish rapport but they really retained their sense of humanity and they were smart and funny. I was continually amazed at the strength of people who go through something like this. It certainly changed them, it certainly had an effect, but for the most part, they are still incredibly funny people. This is so strange to me, to go through an ordeal like this and still maintain your sense of humour. They have very little anger and bitterness which is remarkable.

The other part that surprised me, now that the film is done, is how little pushback we are getting about the film. We get almost no criticism about the film when it comes to the actual issue itself, because we presented it in a way that was very basic, and fundamentally there is no justification for a process like this. I am surprised how even more conservative people are approaching us saying that this process is crazy.

How did you go about building rapport with the men profiled in the film?

It was just about trying to spend time with them, and not always bringing the camera. I wanted to actually let them know that we were there for them and that they would have an opportunity to share their story because we believe that it is an important story to tell. Being upfront with your goal as a filmmaker and an artist is also really important. These are people who have been in the spotlight a lot in a bad way, so we had to show them that the spotlight was theirs and it was their story to tell. It just took time to earn trust, as it is a constant process

Ultimately was this about returning agency to these men?

Certainly. We have heard a lot from the other side, the government side, but what about the voices of the men? The government has its side heard every day and has opportunities to go about things the way it wants. Every day the government puts a tracking bracelet on Mr. Mohamed Harkat without charging him with a crime; it is having its say. Every day that Mr. Hassan Almrei spent in solitary confinement without being changed with a crime, the government was having its say. In our opinion the imbalance existed in real life, and the film was an attempt to correct this imbalance.

Did you get an opportunity to speak with any of the Special Advocates? What do you think about the Special Advocate system?

Who the Special Advocates are is public knowledge, but what they will tell you is restricted. We did have insight about how they feel and about what it’s like to actually go through the process on a very basic level. However, they are not allowed to reveal any specifics about the cases.

The Special Advocate system feels like a very strange compromise that the government and the Supreme Court agreed upon. These half-measures do not address the principle of the issue. The principle is that a person accused of a crime should have access to the evidence against them. There is no substitute for a knowing the case against you. This is important even from a psychological standpoint, if you think about it as one of the people going through it. There may be a lawyer that sees the secret evidence, but you are still in the dark about the case against you. There is no actual solace for you in this process. The Supreme Court did not address this in its decision and I think this half measure does not address the fundamental issue that we need to be talking about. . .

What is next for you? Where do you hope to take this film and this issue?

Our goal is to get the film out to as many Canadians as possible, one way or another. As hard as we worked to get the film made, we have to work just as hard to get the film distributed widely. Not just in schools and theatres but in small communities across Canada.

After we feel that the film has had its exposure in Canada, we will think about where to take it next. I think we will always work around these issues of identity and immigration. There is still a long way for the film to go. It does need to be seen widely and it helps inform the conversation that we are having.

A preview of Secret Trial 5 is now available for free on the website http://secrettrial5.com/

[1] A shorter version of this interview has been published by Rights Review, a journal of the International Human Rights Program (IHRP) at the University of Toronto Faculty of Law.

[1] A shorter version of this interview has been published by Rights Review, a journal of the International Human Rights Program (IHRP) at the University of Toronto Faculty of Law.

[2] The judicial history of the constitutionality of security certificates is long and complex. In 2002, the Supreme Court of Canada upheld the security certificate process as constitutional in Suresh v. Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration), [2002] 1 SCR 3, 2002 SCC 1. However, the court did recognize that deportations to situations of torture do violate a person’s Charter rights, except in “exceptional circumstances.” Adil Charkaoui, Hassan Almrei and Mohamed Harkat all launched further challenges to the constitutionality of the security certificate regime. In 2007, the Supreme Court of Canada in Charkaoui v. Canada (Citizenship and Immigration), [2007] 1 SCR 350, 2007 SCC 9 unanimously held that the security certificate review process which prohibited the accused from accessing the evidence against him was unconstitutional. Most recently, however, the Supreme Court upheld the security certificate against Mohamed Harkat.